The fossil of a small reptile that inhabited Scotland during the age of dinosaurs 167 million years ago has scientists puzzled.

It mixed snake-like traits and lizard-like traits. So was it an early ancestor of snakes or perhaps just an evolutionary oddball? Whatever the answer, it was a formidable little beast.

Researchers said this creature, named Breugnathair elgolensis, possessed teeth that were sharply curved and hook-like, as in snakes.

And the way its teeth were implanted into its jaws and the inward-leaning angle of them relative to the jaws also were snake-like. But its body and head proportions were more lizard-like, including its well-developed limbs.

Breugnathair, which would have been around 12 inches (30 cm) long including its tail, lived in an environment similar to a mangrove swamp with tropical conditions during the Jurassic Period - much warmer than today's Scotland.

Breugnathair may have preyed on insects, small mammals, amphibians and other lizards.

This represents one of the oldest relatively complete fossils from the reptilian group called squamates, which spans lizards and snakes. With its mosaic of features, Breugnathair blurred the line between a lizard and a snake - sort of a "snizard," or perhaps a "liznake."

"Breugnathair is either a lizard-like ancestor of snakes, or it belongs to a more primitive group of lizards that independently evolved snake-like features related to a predatory diet. The balance of evidence is so tight that we weren't able to choose between these two alternatives," said paleontologist Roger Benson of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

"The unexpected combination of features we're seeing shows that early squamate evolution was very complex, and we're only just beginning to understand what might have happened," Benson added.

The earliest-known indisputable snakes in the fossil record date to about 110 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period, according to study co-leader Susan Evans, a paleontologist and evolutionary morphologist at University College London.

"No one would mistake them for anything else. They are long-bodied, lack any trace of forelimbs and have reduced hindlimbs," Evans said.

But these fossils do not reveal what snakes looked like before they evolved their characteristic long bodies.

"So we don't know, for example, whether snakes evolved their distinctive head and jaw traits first, or their long, snake-like bodies first. And we don't know where snakes first evolved, or their ecology," Benson said.

While it is possible Breugnathair was an early transitional form between lizards and snakes, its anatomy is perplexing.

"We know from DNA that snakes are related to iguanas, monitor lizards and some other lizard groups. We therefore expect the ancestor of snakes to be lizard-like, and to share features with those groups," Benson said.

"But when we look at the details of Breugnathair, we don't see many features shared with those. Instead, it has a handful of more primitive features shared with some of the earliest lizards and present today in groups like geckos and skinks. This is a big surprise," Benson added.

Discovered on the Isle of Skye in a coastal locale near the town of Elgol, its scientific name means "false snake of Elgol."

If it was not part of the snake lineage, Breugnathair may have been an evolutionary dead end, with snake-like predatory habits emerging separately in a group that ultimately went extinct, the researchers said.

The earliest reptiles appeared roughly 320 million years ago, Benson said. Some of the earliest forms were superficially similar to lizards but lacked the distinctive features of squamates, such as various traits that increase mobility among skull bones in relation to feeding, and features of the shoulders that increase stride length in lizards.

Breugnathair raises as many questions as it answers.

"It may help us, ultimately, in understanding what traits to be looking for in future fossils to understand snake ancestry," Evans said.

Boosted by Dubai chocolate craze, Argentina bets on pistachios

Boosted by Dubai chocolate craze, Argentina bets on pistachios

At Britain's first plant-based Michelin-star restaurant, most diners aren't vegan

At Britain's first plant-based Michelin-star restaurant, most diners aren't vegan

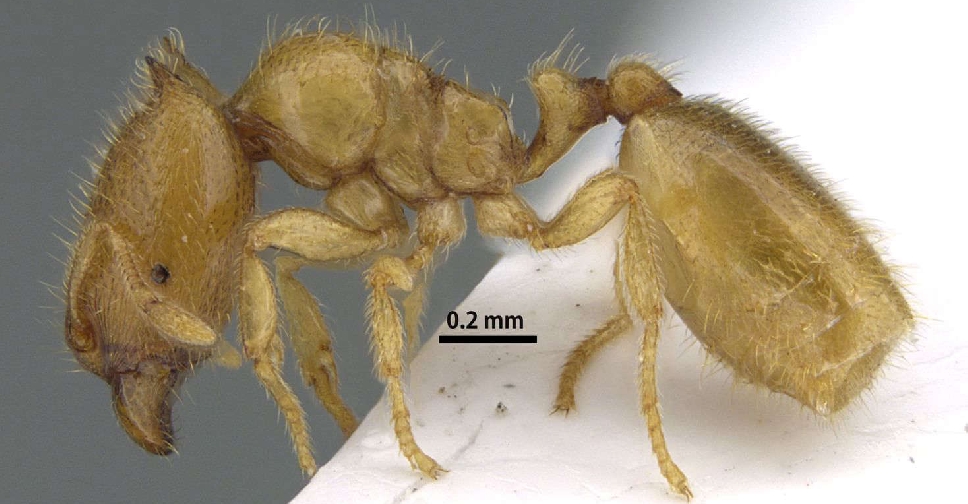

Rare ant species discovered in Sharjah's Wadi Shees

Rare ant species discovered in Sharjah's Wadi Shees

'No strings attached': Meet Paris' pigeon doctor

'No strings attached': Meet Paris' pigeon doctor

'Mimmo' the dolphin delights Venice tourists, worries experts

'Mimmo' the dolphin delights Venice tourists, worries experts